Patients prefer Cannabis vs Opioids

Patients Turn to Cannabis as an 'Exit Drug' From Chronic Opioid Use and Addiction

- Sean Metcalf

Carolyn Evans was in her forties the first time she tried rolling a joint. It didn't go well. "I was all thumbs," she recalled with a laugh.

But the 48-year-old former dental hygienist from Jacksonville, Vt., wasn't doing it to get high. A patient at Southern Vermont Wellness, a medical cannabis dispensary in Brattleboro, Evans suffers from cervical stenosis resulting from multiple car accidents and repetitive work injuries. The degenerative condition compresses her spine and causes severe pain, numbness and weakness in her limbs. After a dozen surgeries, she was unable to work and, in 2013, was deemed 100 percent disabled.

In 2017, after 13 years of taking prescription pain meds, including morphine, fentanyl and oxycodone, Evans began tapering off opioids; by May 2018, she'd quit them entirely.

Evans' pain hasn't disappeared — far from it. But fearful of overdosing on the powerful painkillers and concerned about their long-term health consequences, she decided that cannabis was a safer option. Evans also found it objectionable that if she requested additional pain meds, some medical professionals "stereotyped" her as a drug-seeking addict.

Evans, who's never struggled with drug addiction, now takes a low-dose naltrexone, a medication often used to treat alcohol and opioid dependence. Mostly, though, she uses cannabis to relieve her symptoms.

"I have to say, since I'm off [opiates], I feel a ton better than I did," she added. "I still have pain, but I'm not in a fog all the time. I feel a lot healthier."

Of the approximately 5,200 patients on the Vermont Marijuana Registry, at least three-quarters report using cannabis to treat chronic pain. It's unknown how many use it to wean themselves off opioids or medications, such as methadone and buprenorphine, that are used to treat opioid dependence. Unlike states such as New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania, Vermont doesn't specify "opioid-use disorder" as a qualifying medical condition for the registry. But according to a spokesperson for the Vermont State Police, which oversees the program, anecdotally it's believed that some patients use it for that purpose.

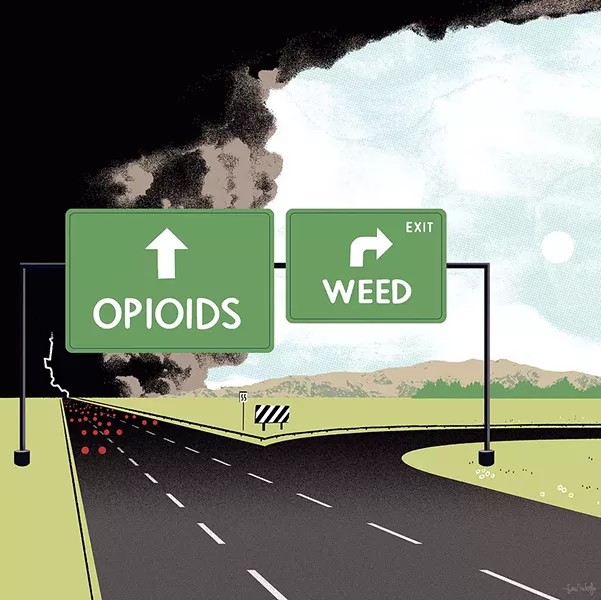

For decades, marijuana was derided as the "gateway drug" that opened the door to more dangerous and addictive substances. But a growing body of scientific evidence suggests that the gateway can swing in the opposite direction. Patients who've taken prescription painkillers for years are now consuming cannabis as an "exit drug" to reduce or eliminate their opioid dependence, as are those with opioid-use disorder who've struggled through vicious cycles of rehab and relapse. Advocates of this approach say that cannabis could be a potent tool for ending America's opioid crisis, which now claims more lives annually than handguns and automobile crashes.

But not everyone is ready to give cannabis therapy the green light. Substance-treatment professionals remain especially wary of this approach, given that many of them treat clients with multiple dependencies that include cannabis-use disorder. While they acknowledge that smoking pot is safer than, say, intravenous heroin use, few seem willing to recommend it to their clients given the dearth of peer-reviewed studies to demonstrate its efficacy on opioid-use disorder.

However, patients are already seeking it out for that purpose. Paul Jerard is a physician assistant with 15 years of clinical experience, mostly in the emergency department at the University of Vermont Medical Center. In April 2018, he founded the Burlington-based Vermont Cannabinoid Clinic, which advises patients in Vermont and elsewhere about how to use cannabis to treat various conditions.

According to Jerard, the vast majority of people who come to him are looking for alternatives to pain meds, including some who have opioid-use disorder. As Jerard pointed out, opioids aren't well tolerated by many patients, especially elders, because they can cause drowsiness, constipation and nausea. "And, of course, there's the ever-present danger of overdosing and dying," he added.

Jerard said he occasionally sees the fortysomething man complaining of "back pain" who really just wants a registry card to get high rather than to get off pain meds. Still, even for patients who won't stop taking opioids, Jerard said that cannabis can be beneficial. "In fact, one of the interesting and encouraging things about cannabinoids is that they work synergistically with opioids," he added.

Indeed, in a paper titled "Emerging Evidence for Cannabis' Role in Opioid Use Disorder," published online in the September 1, 2018, issue of Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research, researchers found that by combining cannabis with opioids, patients achieved the same level of pain relief at lower opioid dosages, thus reducing their risk of accidental death. In 2017, 101 Vermonters died of non-suicide opioid overdoses, including 33 who succumbed after taking too many prescription meds.

One of New England's most ardent advocates for using cannabis to stem the opioid crisis is Dr. Dustin Sulak, an osteopathic physician and medical director of the Falmouth, Maine, office of Integr8 Health. His practice's 16 health care providers in two offices in Maine treat more than 20,000 patients, many with medical marijuana.

Sulak answered questions from Seven Days via email and also referenced his May 10, 2016, public lecture "Cannabis as a Solution to the Opioid Epidemic," held at the University of Southern Maine in Portland. Sulak explained how cannabis can tackle some of the most intractable problems associated with the opioid epidemic. Adding cannabis to opioid regimens, he said, enhances their painkilling properties while also preventing patients from developing a tolerance to them, thus reducing the need to escalate their dosage.

Sulak pointed to a 2016 Michigan study of 244 medical cannabis patients who were using cannabis for pain. Patients reported a 64 percent decrease in opioid use, fewer side effects from other medications and a 45 percent improved quality of life. He also cited a 2014 study, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, which found that states with medical marijuana laws had, on average, a 25 percent lower rate of accidental opioid deaths.

As for patients already struggling with addiction, Sulak said that cannabis is effective in treating opioid withdrawal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, cramping, muscle spasms, anxiety, agitation, restlessness and insomnia. And its safety profile is better than buprenorphine and methadone, he noted, both of which pose greater risks for abuse, diversion and accidental death.

"I'm not putting these treatment options down," Sulak clarified. "These treatments save lives ... but they're not enough. We need something more."

Cannabis, Sulak contended, can also change opioid-dependent brains by promoting neuroplasticity, or physiological changes in their structure related to forging new behaviors and thought patterns. "That's exactly what we need to get someone out of that addictive cycle into a new phase in their life."

Because addiction is known to have a genetic component, relatives of people with substance-use disorders are at heightened risk of developing addiction problems themselves. When Windham County resident "Kay" was seriously injured on the job in 2007 by lumber that blew off a trailer and knocked her down, she was left disabled with four rods in her hip. Despite persistent pain that made her unable to work for three years, Kay refused to take opioids. Kay had never struggled with drug addiction, but her sister did, and Kay didn't want to go down the same path.

At the time of Kay's injury — and to this day — her sister has been hooked on opioids. A registered nurse who was herself injured on the job, she eventually lost her nursing license after getting caught changing a patient's prescription and stealing meds from another. Kay's nephew was born opioid dependent and was taken from his mother for the first year of his life. As Kay put it, "It was a horror story."

Since 2007, Kay has used cannabis to treat her pain. (She's on Vermont's marijuana registry and asked that her real name not be used out of concern that it might affect her employment status.) Though she never consumes cannabis before work, she uses it daily for pain, typically by smoking or vaping it and by consuming edibles and cannabis oil.

"My sister and her situation really scared me, to be honest," she said. "Opiates are such a sad, sad situation right now."

But it's not the responsible cannabis user, like Kay, that Kurt White worries about. White is a social worker, a licensed drug and alcohol counselor, and director of ambulatory services at the Brattleboro Retreat. For four years he was also president of the Vermont Association of Addiction Treatment Providers, which represents about 20 treatment organizations statewide.

White, who's been involved in substance-abuse treatment for more than two decades, said that using marijuana as a substitute for harder drugs is nothing new. For years it was referred to, somewhat tongue-in-cheek, as "marijuana maintenance."

Most people, he acknowledged, can use cannabis and never develop problems with it. He's mostly concerned about the 10 to 15 percent of the population who lose control over their consumption and become addicted, especially young people and those with mental health problems.

"Those negative consequences [of marijuana use], on the whole, are of a lesser magnitude than the negative consequences associated with something like IV heroin use. But it doesn't mean they're nonexistent," he added. "And people who have an existing addiction to one drug are much more likely to have an addiction to other drugs."

Moreover, if you look at the population addicted to opioids, he said, they tend to be very heavy cannabis users who consume it in compulsive ways.

Still, like many substance-treatment professionals, White said that he subscribes to the idea of "patient self-determination as a core value of our profession." That is, patients will make their own choices, and if they choose a path that's less harmful than another one, he'll support their decision. Still, that doesn't mean he's ready to recommend cannabis based on the current body of clinical research.

"Being professional providers, we generally go where the evidence leads us and try not to jump the gun," he added. "The science just isn't there yet."

Correction, May 16, 2019: An earlier version of this story misidentified the location of an Integr8 Health office. They have two offices in Maine.